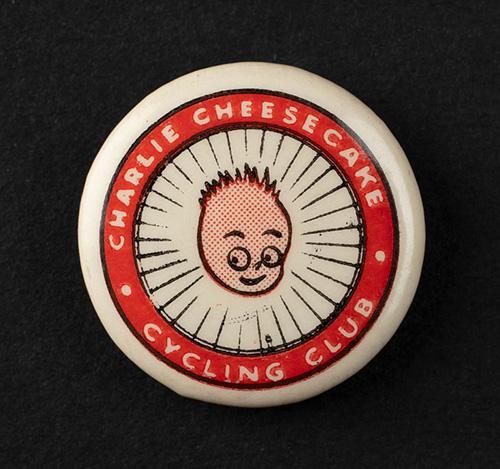

Don't touch that dial! Children’s radio club badges and pins

History rescued from the rubbish to tell a tale

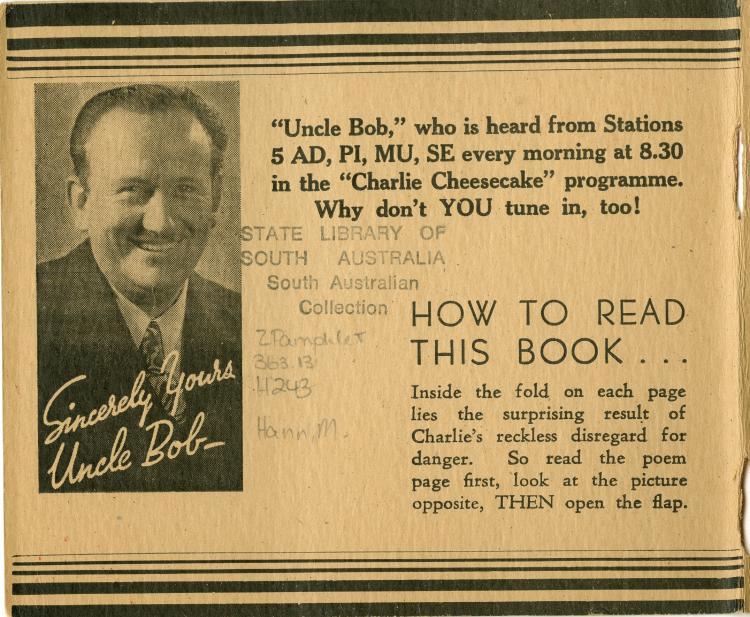

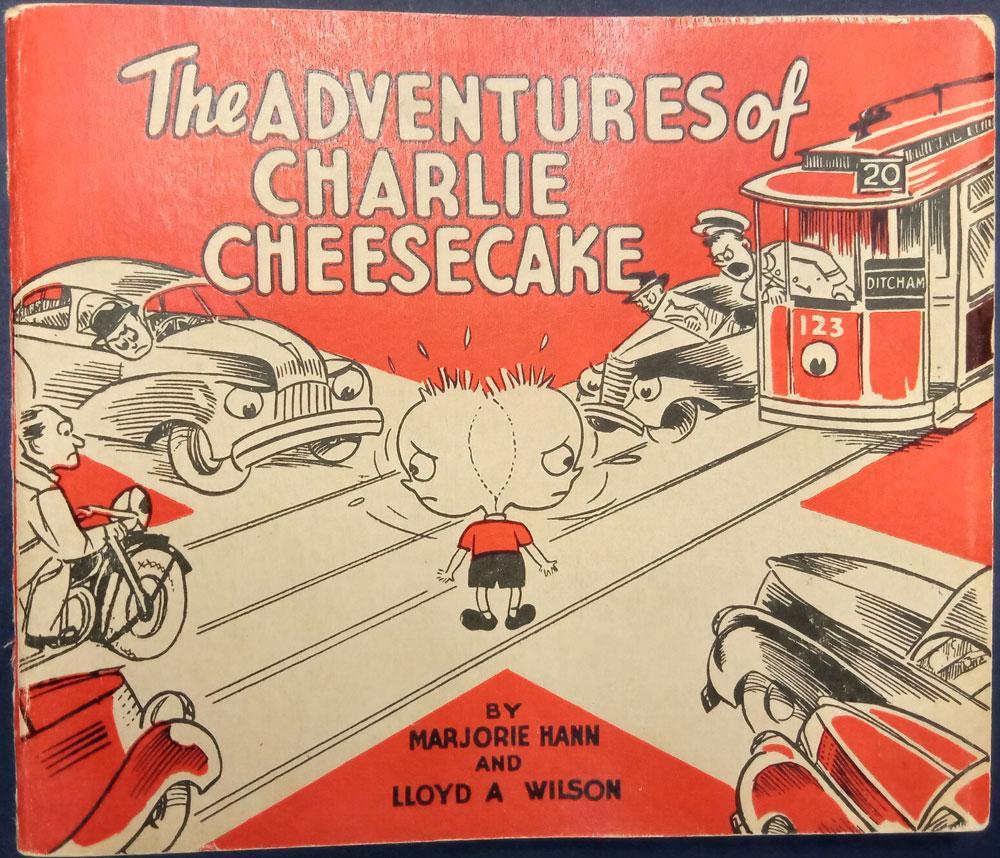

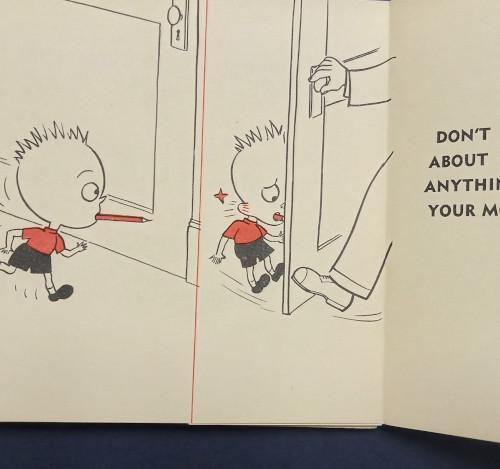

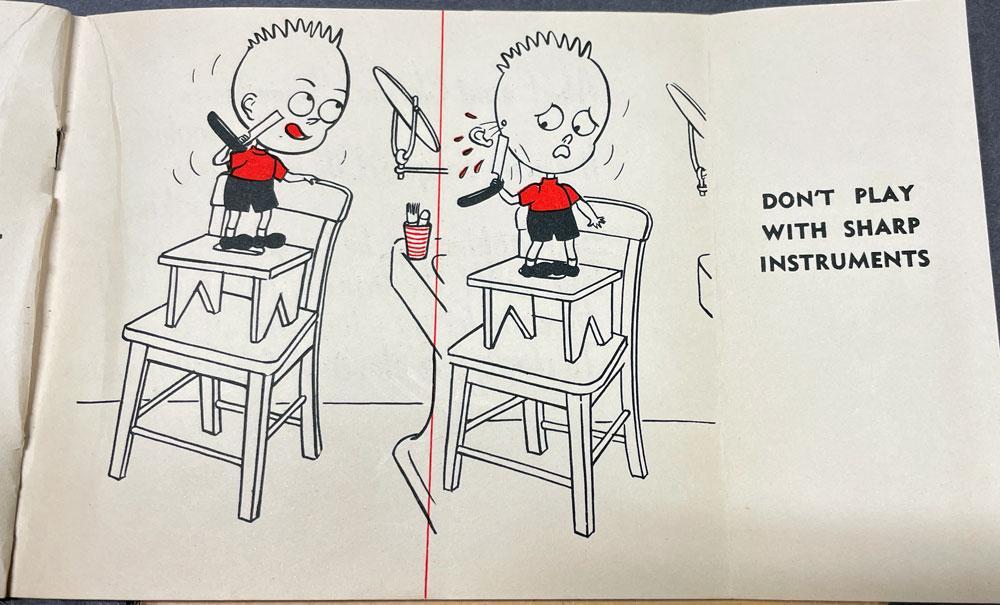

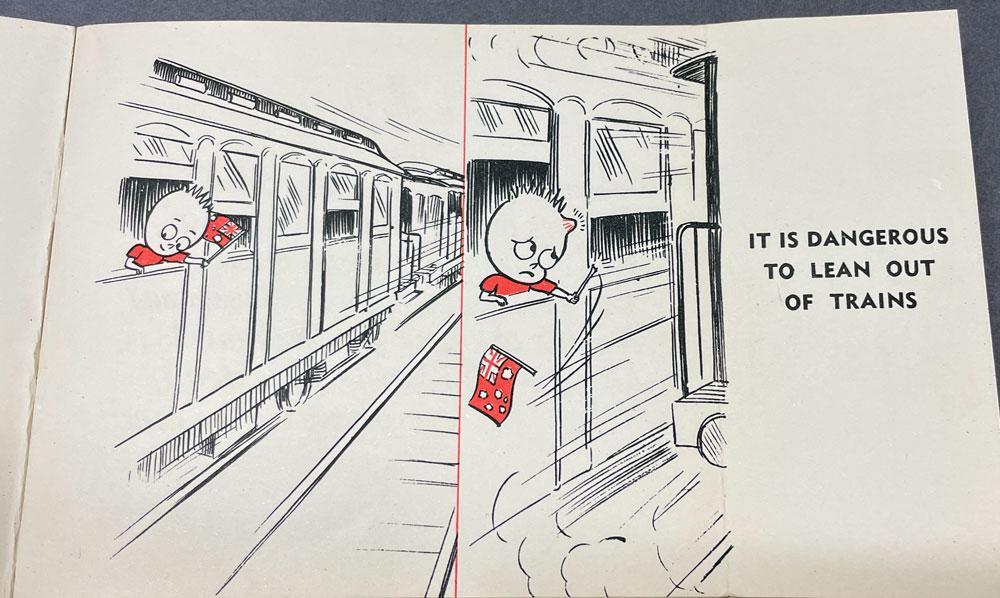

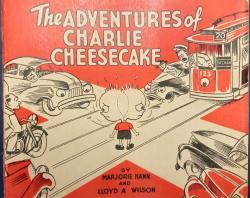

Marjorie lamented ever after that she was identified with ‘Charlie Cheesecake’, rather than the fine arts she practiced at the South Australian School of Arts and Crafts.

Who else was on this journey with ‘Charlie Cheesecake’?

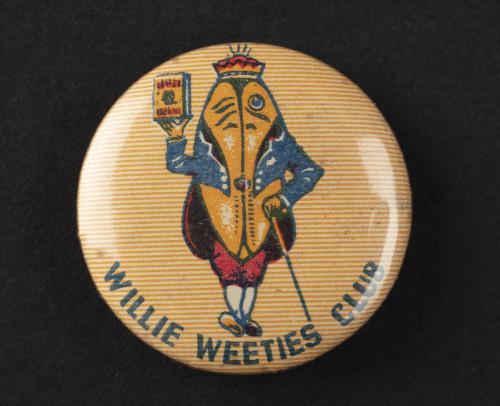

Charlie was graced by the majestic presence of ‘King Willie’, a regal wheat kernel promoting the ‘Willie Weeties’ cereal club. Children who ate this cereal could write away asking to join the cereal club and receive a badge by return post. According to the return address on His Majesty’s correspondence[2], the ‘King of Cereals’ resided in Fremantle, Western Australia. This was probably somewhere near the North Fremantle factory where Weeties were manufactured until the mid-1990s and from whence in 1937 a children’s sing-along radio show was broadcast. On Saturday mornings huge crowds attended Willie Weeties Community Concerts at Boans Department store in Perth city, and children sang along with the Weeties song lyrics which were screened at the front of the hall. Our research has also uncovered other Weeties marketing formats such as a Weeties recipe book held by the National Library and advertising on a board game called Football Game also held by the State Library of South Australia.

An oddly assorted companion

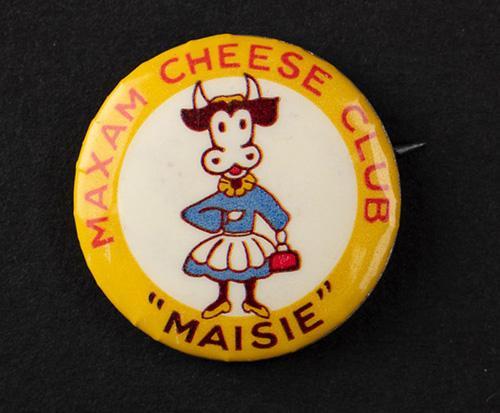

On the more demure side, we have ‘Maisie’ the Maxam cheese cow. The person who found these badges believed this to be a talking cow from the 1950s 5KA children’s program, though we could not confirm this. Perhaps there is an enthusiast out there who can help us with more information?

What we do have is another appealing character used to influence household purchasing decisions, through children. The Maxam company manufactured processed cheese out of Queensland, in an era when ‘ration pack' food with an unlimited shelf life was considered quite acceptable to eat. Needing no refrigeration, this immortal cheese was transported across Australia hence almost anyone who was a child in the 1940s and 1950s would have eaten it. Children received a coloured badge when entering a newspaper caption competition or jingle competitions using the inside of a Maxam cheese pack to write their entry. Newspaper advertisements of the time boasted that the flavour of this cheese ‘never varied’.[3] What a relief.

The rank outsider

This pin is the odd one out in the set, displaying a futuristic zig-zag radio signal flashing across the 5KA logo rather than a character. From 1939, this radio club was a huge social phenomenon for South Australian children.

During the 1950s, the Adelaide 5KA Smilers’ Club was broadcast each weekday afternoon at 5pm with presenters Uncle Jack Fox and Aunty Margaret Baker (Doreen Govett).[4] This listener’s club was very social and provided access to cultural events, poetry writing competitions, boat rides, and children’s parties at venues like the Adelaide Zoo[5], where fans could meet the presenters and try for an autograph amongst the throng of other club members. The hosts even broadcast visits to children in hospital.

The announcers obviously had other roles at the stations, broadcasting shows especially for ladies, or revolving around sport, but the kids revered these radio identities for their friendly, charming personas and wore their ‘radio wave’ club pin with pride. Some would say this sort of innocence and social cohesion no longer exists. Whether this is true or not, the Smilers’ Club was mandatory listening for thousands of kids.

A most charitable character

This 1954 hound-like character pin was issued to members of the Radio 5AD Dog House Club and is the only pin in this set with the actual issue date forged on it.

From 1951, the Dog House Club’s ‘kennel master’ announcers were crucial in raising money, with the sale of the pins, for the current Women’s and Children Hospital, as the existing Adelaide Children’s Hospital (built-in 1876), was too small, worn out, and in financial trouble.

The charitable appeal began early in the year, and children were promised that radio personalities would read out the name of every child’s pledge on Good Friday, so there was always that chance to hear your own name. Club membership entitled you to a certificate endorsing you as a ‘doggie’ and entry to other club activities staged to raise money. At these social events, members could buy another badge, the design of which changed over time to maintain interest. Many children had more than one pin and anecdotally people still find them in back yards, on outback roads, and in boxes of family papers. Or on suburban streets, such as this example.

The charity campaign was hugely successful, and the money was matched by government funding. On 19 April 1954, The Advertiser[6] reported a record £27,520 had been pledged and asked people to bring the money to the front desk of the newspaper.

Children wore their Dog House Club badges with honour as then people would see that they had supported the Hospital appeal. Parents approved the donations as they knew the hospital would benefit the entire community. The appeal continues today using television and other social media as the marketing method.

Lastly, a less troublesome Charlie?

How ‘Charlie Chuckles’ got mixed up with ‘Charlie Cheesecake’ on a piece of cardboard is anyone’s guess. It could be explained by border proximity. Or perhaps their reputations had something in common?

In a partnership between different media, ‘Charlie Chuckles’ the kookaburra characterised both a children’s newspaper club in the Sunday Telegraph (Sydney) and a Sunday radio show broadcast in New South Wales between 1941 and 1954. The shows were pre-recorded in Sydney then sent to stations all over the state including an audience of child listeners in Broken Hill,[7] close to the South Australian border.

Children aged under 16 were eligible to join the Charlie Chuckles club and receive a kookaburra pin. During the radio show, the newspaper club comics like Superman and Popeye were 'read out' in the fashion of traditional radio dramatisations, in a very hammed-up manner. Club membership offered children the chance of a call-out on their birthday and sometimes even clues as to where their present was hidden. Only club members were entitled to enter the lucrative club contests over poetry and colouring-in, which offered cash prizes.

Originally the character, ‘Charlie Chuckle’ with no ‘s’, was voiced by the ‘King of the Cads’, stage and radio actor Arundel Nixon, a notorious fellow by most accounts on TROVE. His early death at age 42 (theatrically predicted by a fortune-teller)[8], necessitated the sudden change in ‘Charlie Chuckles’ voice to the more reputable Howard Craven. This development went unannounced by broadcasters but certainly not unnoticed by dedicated young listeners.

From the mid-late 1950s, television began to take over Australian children’s interest in radio shows, and they switched their loyalty to television shows and clubs. The imported Mickey Mouse Club had instant appeal, and Adelaide’s own Romper Room and The Channel Niners offered local children the chance of an appearance on television, placing them in the story of the show.

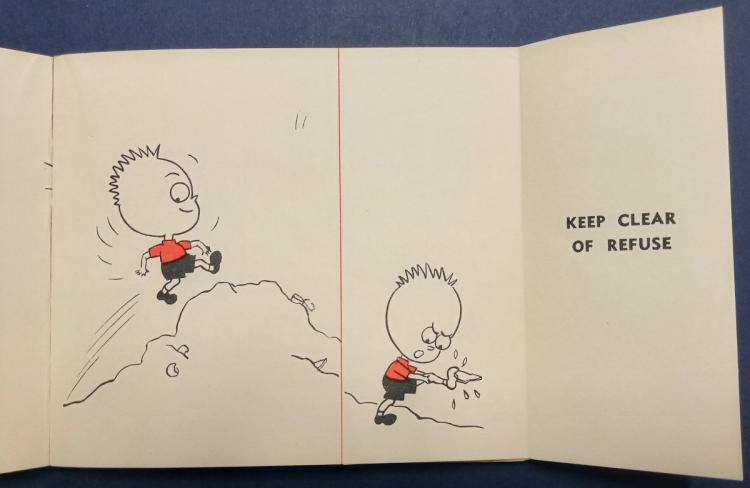

‘Keep clear of refuse’ they told ‘Charlie Cheesecake’. Nonetheless, he found himself in a pile of roadside rubbish, clearly engaging in his usual risk-taking behaviours. And he even took several friends with him! Thankfully, an alert passer-by realised the badges and pins were a part of South Australia’s history, and although you shouldn’t really pick rubbish up off the ground (because it’s dirty) we are fortunate that in this case, he did.

references

[1] Kyle Asquith (2014) Join the Club: Food Advertising, 1930s Children's Popular Culture, and Brand Socialization, Popular Communication, 12:1, 17-31, DOI: 10.1080/15405702.2013.869334 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2013.869334.

[2] Carnamah Historical Society and Museum, accessed 21 April 2021.

[3] The West Australian, Tue 9 Feb 1954, page 8 , accessed March 2021.

[4] Interview with Doreen Govett and Lionel Williams, State Library of South Australia, 1996, OH 309/13.

[5] Children at party, The Mail, Adelaide, 13 March 1954, page 12.

[6] Good Friday Appeal, The Advertiser, Adelaide, Monday 19 April 1954, page 2.

[7] Ravlich, Robyn, Skywriting: making radio waves, [Blackheath, New South Wales] : Brandle and Schlesinger, 2019, Chapter 2.

[8] Death was predicted, Brisbane Telegraph, Tuesday 5 April, 1949, page 7.

Griffen-Foley, Bridget, Prof., Australian radio listeners and television viewers : historical perspectives, Cham, Switzerland : Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Ross, John F., A history of radio in South Australia, 1897-1977, Plympton Park, J Ross, 1978.

TROVE, the National Library of Australia’s digitised Australian newspaper database.

Written by Denise Chapman, Curator - Engagement

![Baby leaning into a radio, 1938-1960, Raymond Heir Gordon. [SLSA: PRG1605/6/95]](/sites/default/files/styles/wysiwyg_embed/public/2021-11/baby-leaning-into-radio-PRG1605-6-95.jpg?itok=IZ-l5ppV)