Elizabeth Woolcock – murderer or victim?

A South Australian true crime.

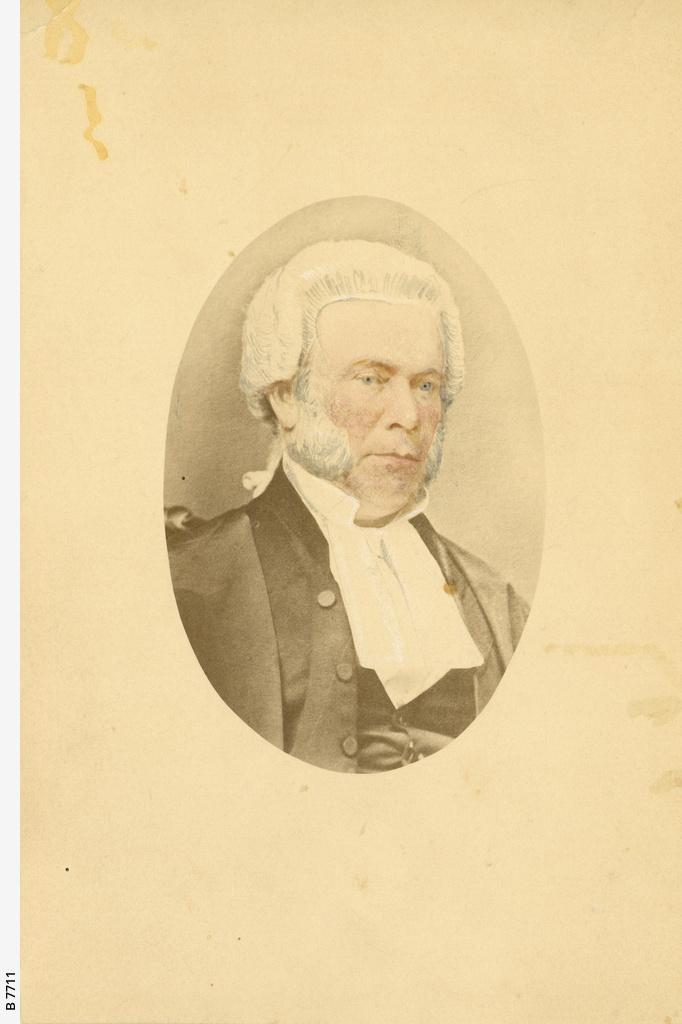

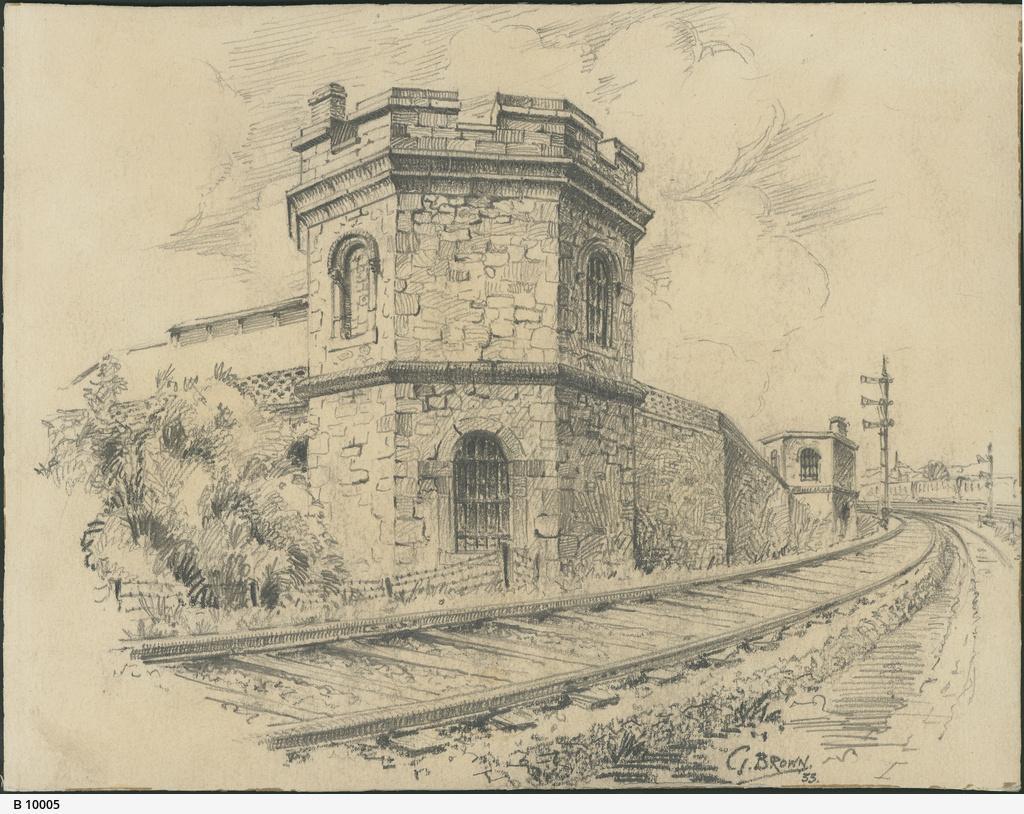

Elizabeth Woolcock was sent to stand trial at the Supreme Court in Adelaide. A jury took less than half an hour to find her guilty. Despite their recommendations for mercy given the conflicting medical evidence, and the lifelong abuse she had suffered, the judge (Mr Justice Wearing) sentenced her to death. By law, the judge had to put the jury's recommendation for clemency to the colony's governor and offer his opinion. This was not granted. On 30 December 1873, Elizabeth was hanged in the yard at Adelaide Gaol. She was 25 years old.

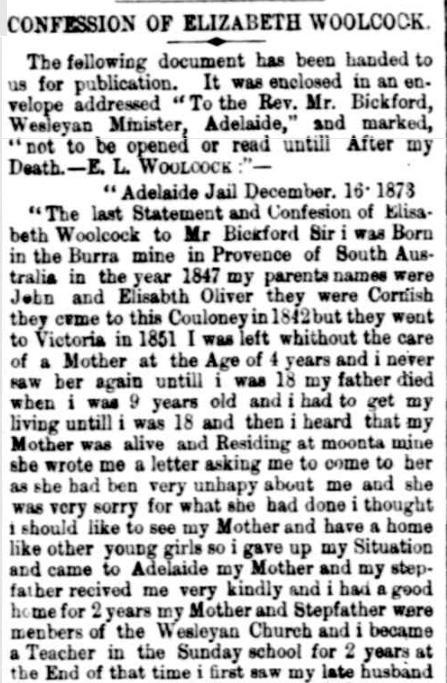

Two weeks before her execution, Elizabeth wrote a confession and handed it to the Reverend James Bickford, who had been visiting her in the Gaol, with the instruction that it be opened only after her death.

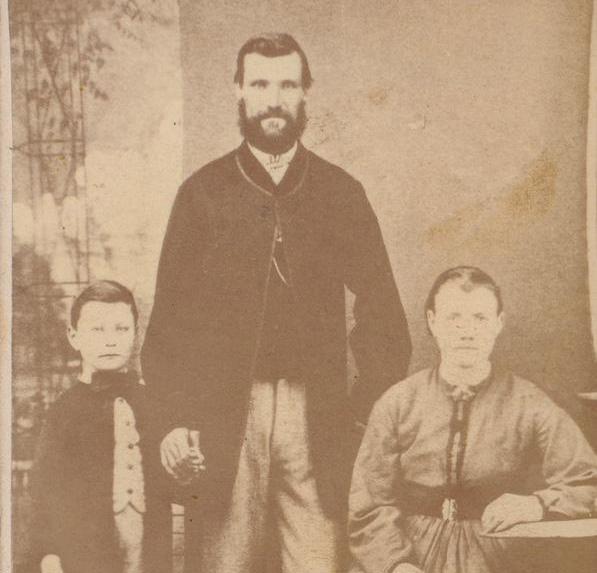

In the years since her execution, questions have been raised over whether she did commit this crime, or whether it was accidental or the result of medical incompetence. Doubts about her confession have also been raised. Not only the trial but the judgement of the strict Methodist family and community to which she had returned, and her increasing need for peace may have contributed to what she wrote. The confession begins as a brief biography but becomes increasingly more religious and fervent in tone 'satan tempted me and i gave him (Thomas Woolcock) what i ought not.'

Elizabeth' short life was filled with tragedy from early childhood to death. Abandonment, grief, pain, sexual violence and physical abuse were constant companions. Even if she was responsible for his death, surely there was room for compassion. The jury thought so. The judge did not. Did she do it? And if so, did the punishment fit the crime?

Do you think Elizabeth killed Thomas Woolcock? If you want to find out more, the following books are available to read within the State Library, or you could search for them at your local library.

More to explore

Books:

Peters, A.L. (1992). No Monument of Stone.

Peters, A.L. (2008). Dead Woman Walking.

Ralfe, Dawn Joy, (2013) Murders and mayhem at Salt Creek

Newspaper reports:

'Confession of Elizabeth Woolcock,' South Australian Register , 2 Jan 1874, page 5.

'Execution of Elizabeth Woolcock,' Wallaroo times, 3 Jan 1874, p 3.