The 'Celestials' in South Australia

A short story to celebrate Chinese immigration in South Australia.

In May 1851, the significant gold deposits discovered across Victoria and New South Wales (NSW) led to a surge in mass immigration. Heavy poll taxes were imposed on the Chinese by the eastern colonies in an attempt to dissuade them from coming. As a result, many found it cheaper to come to South Australia by ship, then travel overland to the goldfields, rather than sailing directly to Victoria or NSW. As a result, numerous so-called 'Celestials' only stayed briefly in South Australia before moving on.

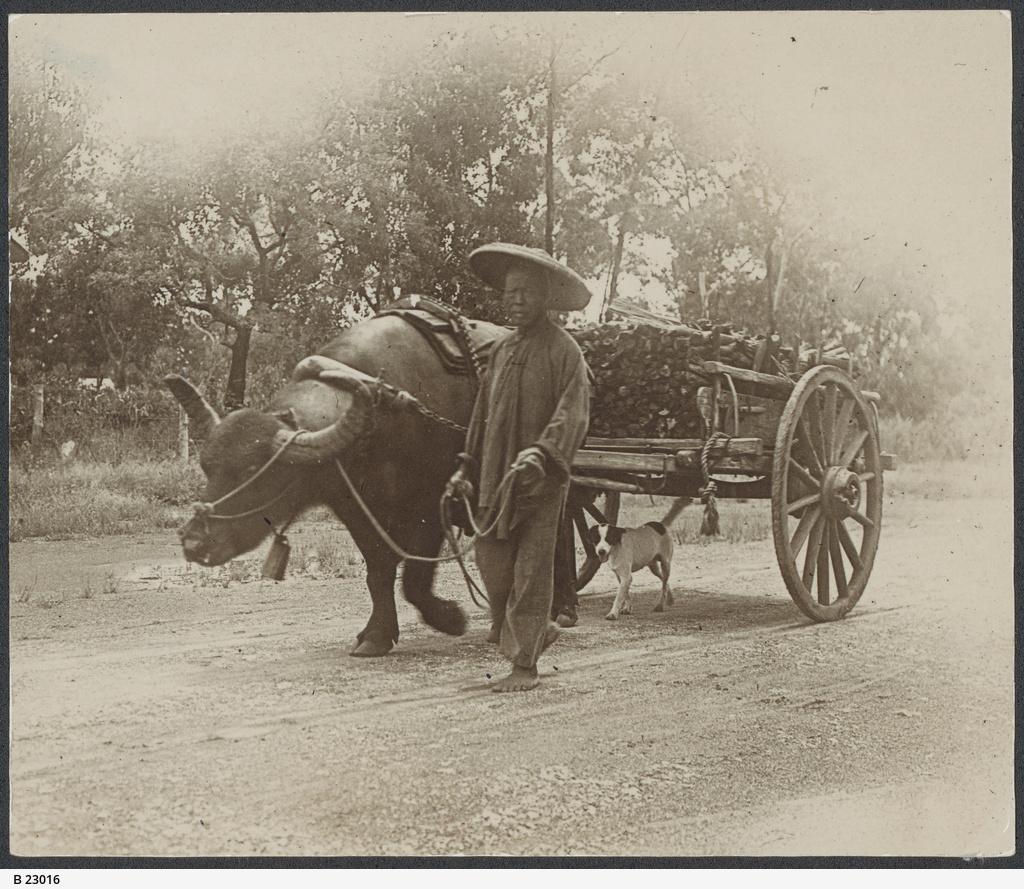

Because American and British captains were unfamiliar with harbours along Australia's southern coastline, they would transport their passengers to Port Adelaide. From there the new arrivals would travel overland, usually in highly organised groups. They would walk along the 90-mile-long Coorong lagoon to reach Victoria's Ballarat and Bendigo goldfields. Roads didn't exist at the time, so the journey, which spanned almost 800 kilometres, was arduous and required making passage through sand and scrub. Along the Coorong Salt Lake route, the Chinese would dig a series of wells to ensure fresh water for themselves and people who followed their trail.

If you visit the area, you will see signs that commemorate the wells' construction and refer to the trip as a ‘Journey to Gold’. Between 1857 and 1863 over 17,000 Chinese people walked from Robe to the Victorian goldfields.

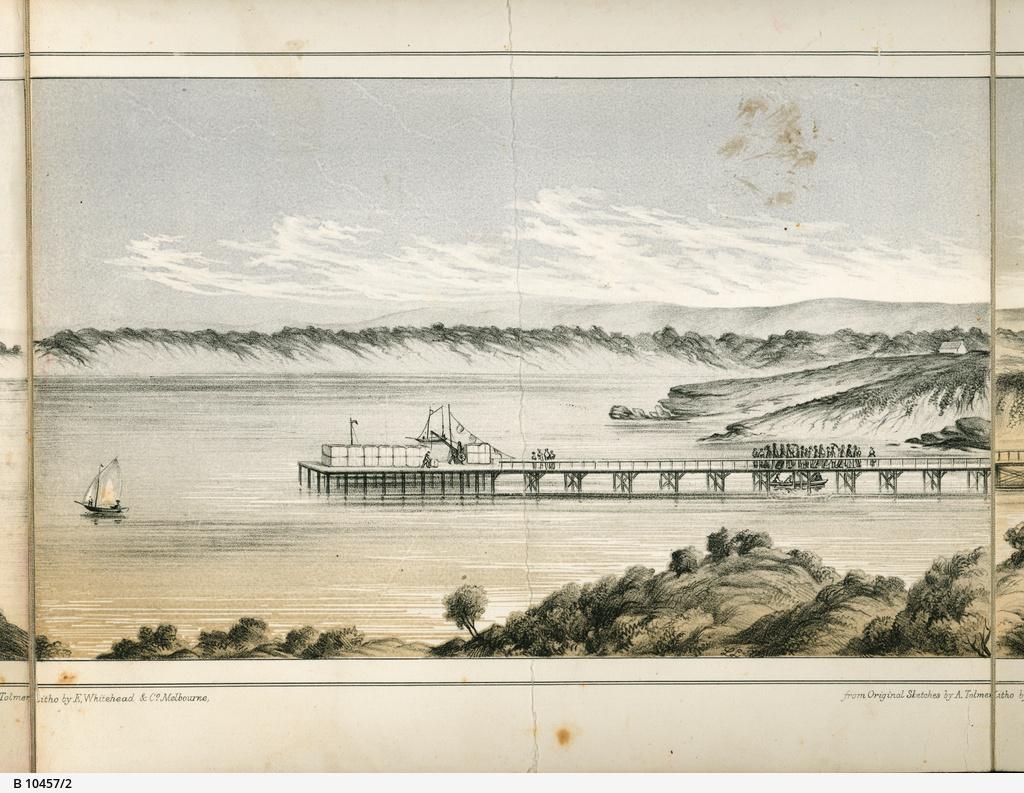

By the late 1860s, ships' captains were becoming familiar with the South Australian coastline and realised that they could sail directly to Robe. The town’s locals rapidly created businesses to transport the new arrivals from the ships to the shore and sell them supplies, usually at vastly inflated prices. An arrivals tax was imposed and a new Customs House was soon built to enforce its collection.

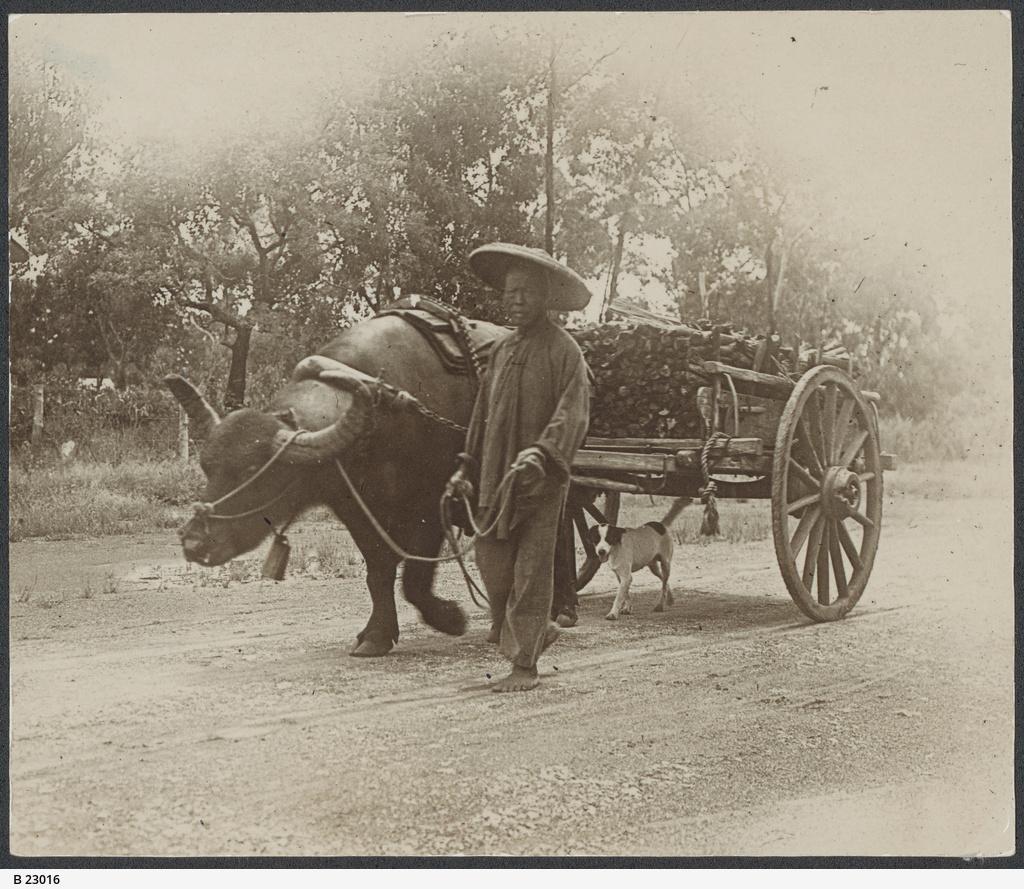

As the gold mining boom faded, most of the 'Celestials' returned home to China or moved on to new goldfields in places like New Zealand. Those who remained settled mainly in the eastern colonies or the Northern Territory which was under South Australian jurisdiction from 1863 and 1911. In South Australia itself, the number of Chinese immigrants began to rise in the 1870s and 1880s with new arrivals working in market gardens, on riverboats, running laundries or running small eating houses. Some also worked on the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line.

Sadly, hostility grew between the Chinese and Europeans with language and cultural barriers proving hard for the recent immigrants to overcome. Anger increased over Chinese workers undercutting the existing European labour force and opium addiction became a major issue in the late 1800s. History shows that it was the British who created the original problem by importing opium to destabilise Chinese society. This led to the Opium Wars of the mid-nineteenth century which forced the country into unfair trade agreements with Britain and Europe. However, it was generally assumed that the subsequent spread of drug use was solely the fault of the alien 'Celestials'. Throughout the Australian colonies, there was an exaggerated fear that Chinese opium dens would destroy the British Empire.

In 1901 the growing hostility prompted the newly formed federal government to enact the Immigration Restriction Act. This legislation formally instituted what we now refer to as the White Australia Policy. This focused on those of Asian heritage but encompassed all non-white individuals. Curiously, the two main groups who opposed the Act were British shipowners, who heavily relied on Chinese passengers and non-white crews, and the Japanese, who were incensed at being grouped in with the Chinese.

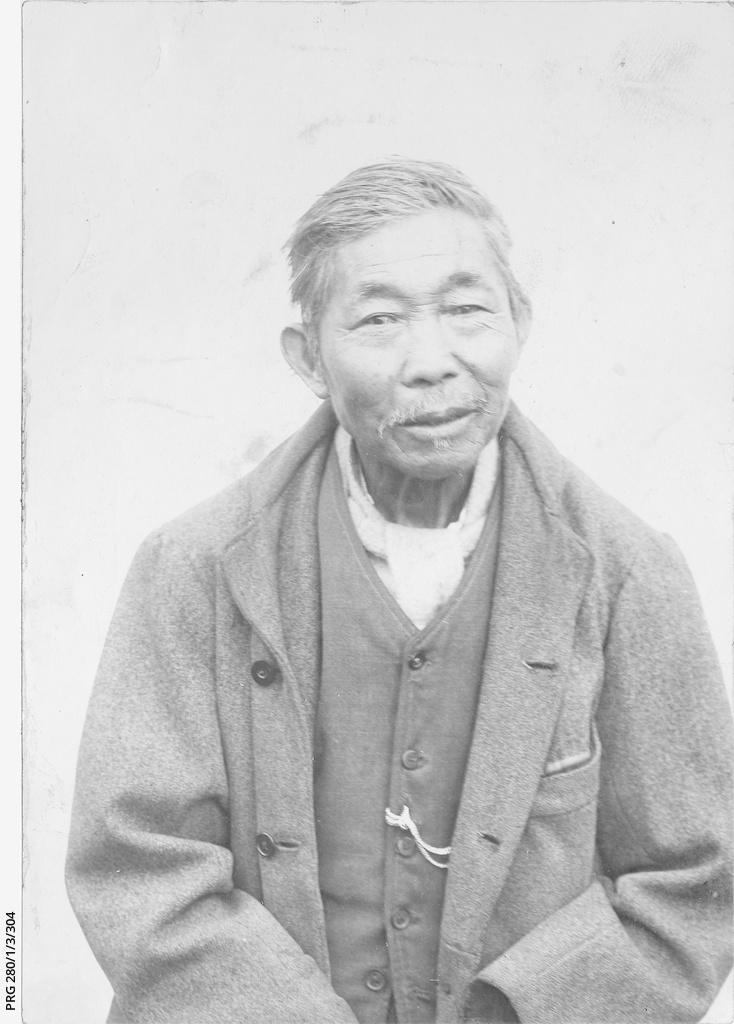

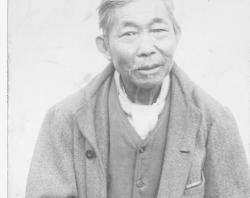

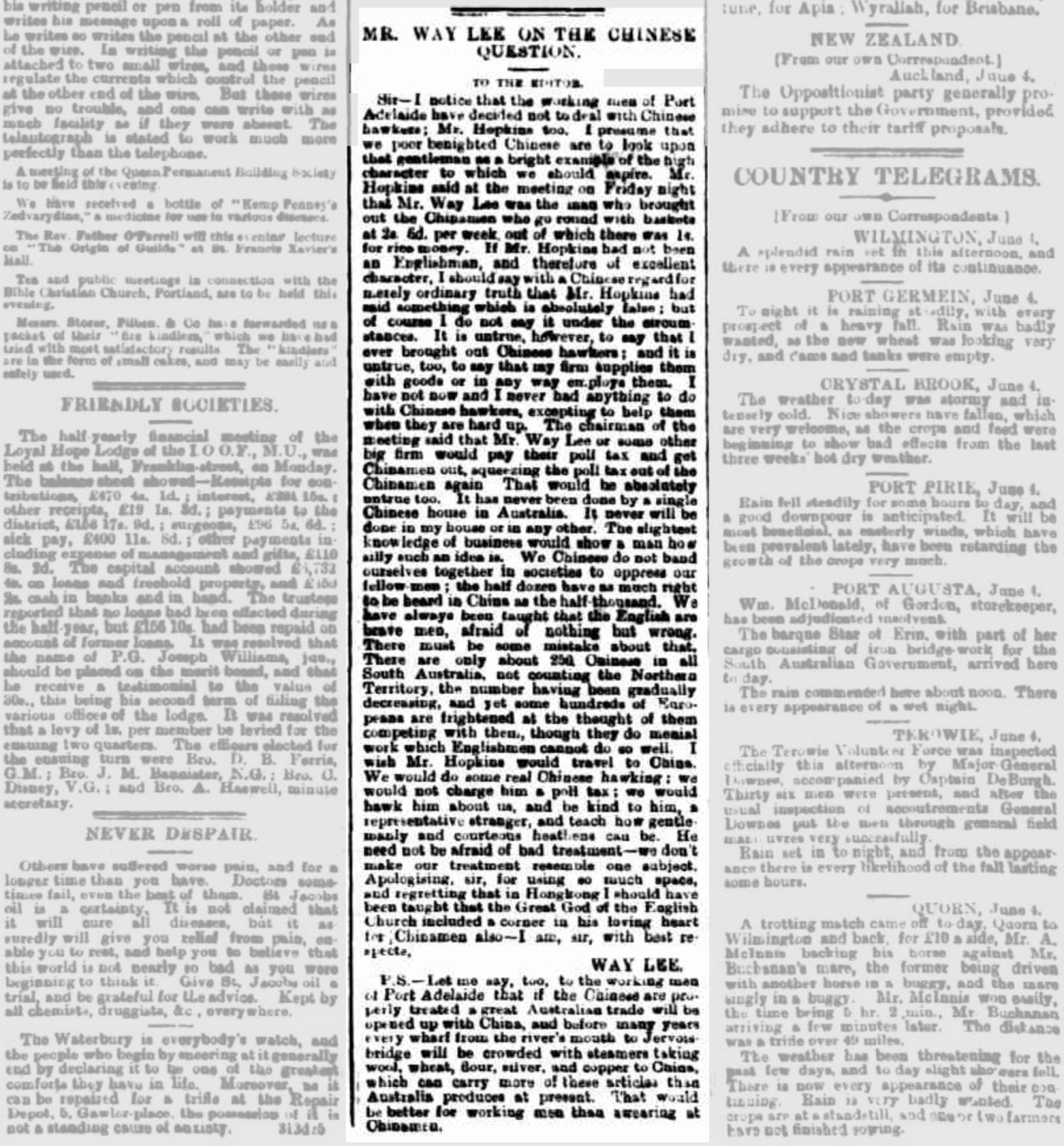

By the early twentieth century, South Australia was home to several prominent Chinese entrepreneurs, some of whom articulated compelling and rational opposition to the Act, without success. One such figure was Yett Soo War Way Lee, known as Way Lee. He had initially migrated from Canton, China to Sydney before relocating to Adelaide to establish a thriving import business. Way Lee had been naturalised in 1882 and he used his considerable influence within the community to reduce anti-Chinese prejudice and discrimination. He introduced Chinese New Year celebrations to the South Australian social calendar and became a Freemason.

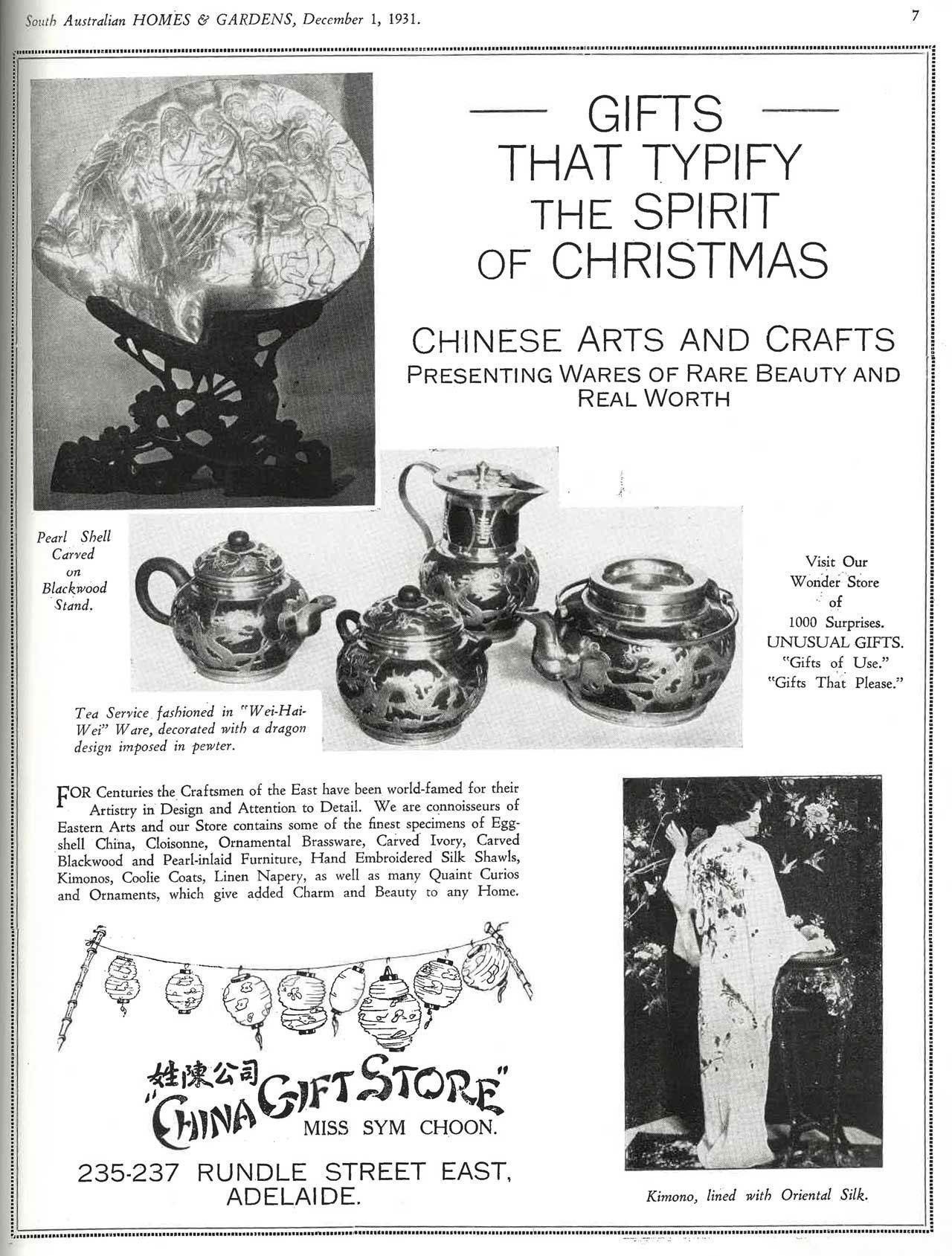

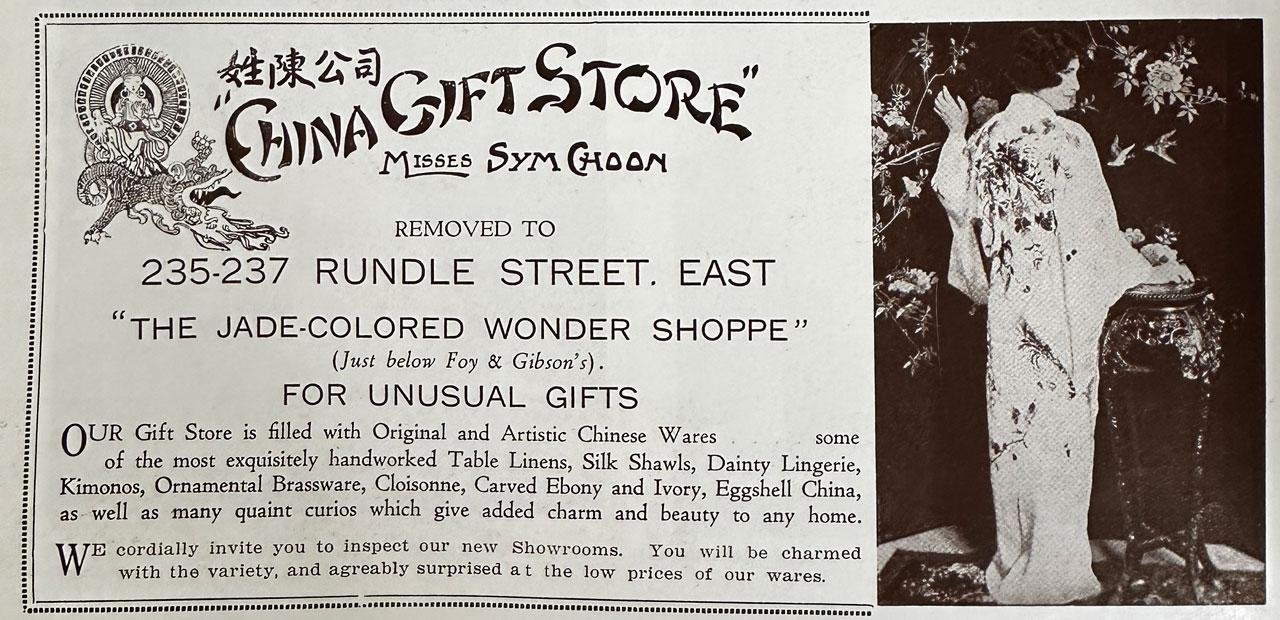

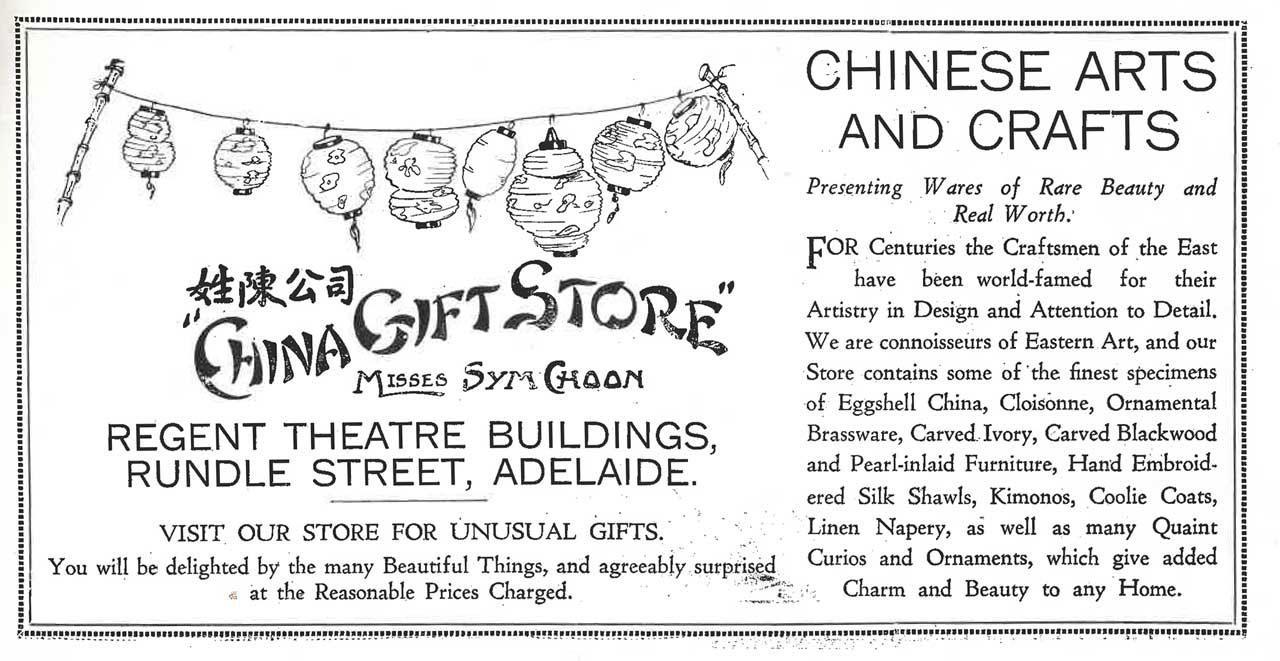

Despite blatant racist policies such as the Immigration Restriction Act, there remained a strong fascination with the enigmatic and ‘mysterious East’. Artworks depicting men and women in traditional Chinese dress and imported goods like embroidered clothing and decorative Asian homewares were very popular.

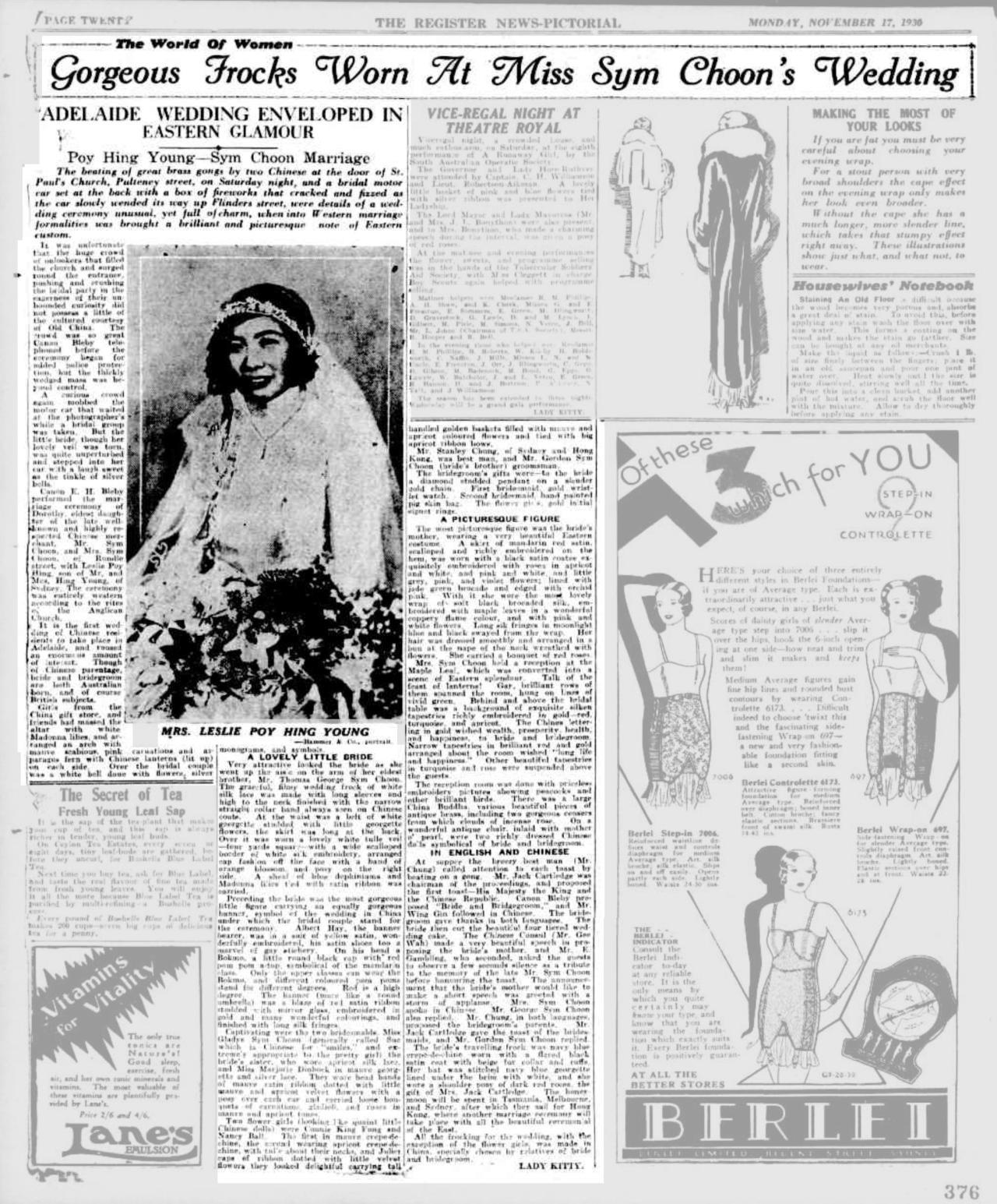

These exotic oriental goods proved so popular that in the 1920s, Gladys Sym Choon and her sister Dorothy, whose parents had migrated to Adelaide from Guandong province in the late 1800s, opened the China Gift Store on Rundle Street. They were so successful that they soon opened a second store in nearby Regent Arcade. The stores were eventually sold but the Rundle Street shop, now a fashion outlet, retains the name Miss Gladys Sym Choon.

In addition to being successful businesswomen, Gladys and Dorothy were considered fashion icons and trendsetters during the 1920s and 30s. At Dorothy’s wedding, people lined the streets trying to glimpse the glamorous Sym Choon sisters. This is strongly at odds with the notions that underlay the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act.

The story of Chinese immigration in South Australia is a long and complex one. It spans more than 150 years marked by resilience in the face of hostility and progress despite discrimination. The White Australia policy is dead and gone but echoes of racism still linger and ugly voices still bleat out their intolerance. Despite these throwbacks to a meaner time, the majority of Australians want to live in a truly inclusive multicultural society. Living in harmony is worth working for. Harmony is worth celebrating.

Written by the Engagement and Marketing team

More to explore

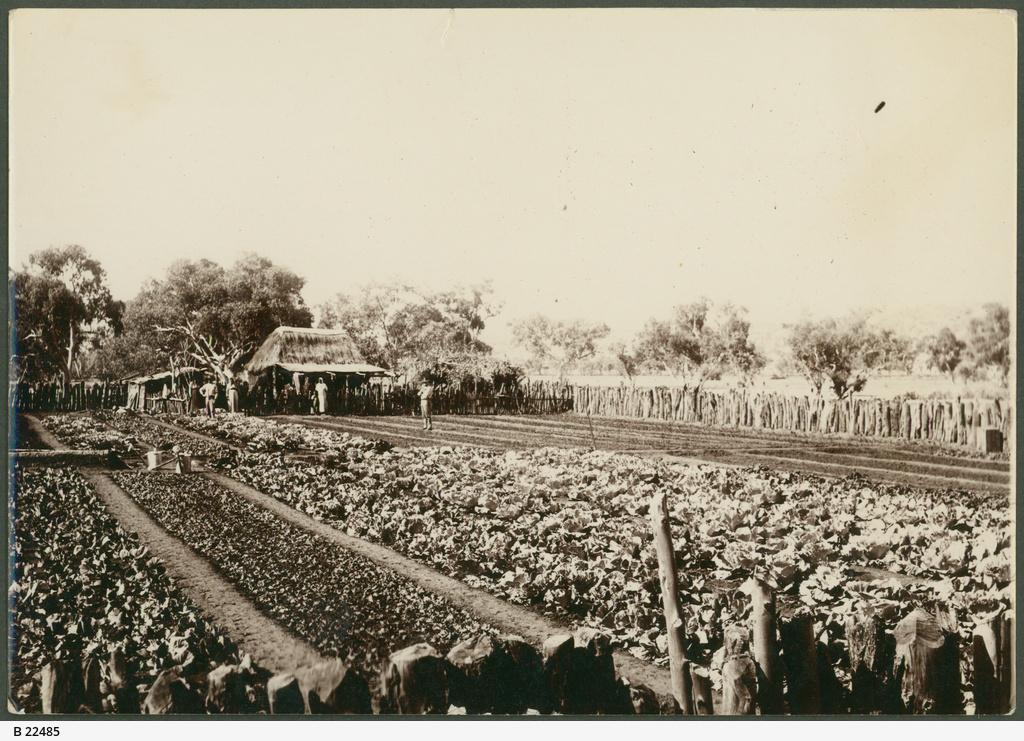

A Chinese Market Garden at Oodnadatta. Ned Chong's story is a fascinating testament to resilience, adaptation, and community growth in the face of challenging circumstances. His journey from China to Australia, his business partnership with Cherry Ah Chee, and his eventual marriage to Minnie reflect both the divisions and integration inherent in Australian cultural history.

How did Australian children experience the Overland Telegraph Line? The State Library has delved into the collections and discovered a story that explores the Australian child as an observer, mimic, student, servant, labourer, standard-bearer, orphan, and casualty of the Overland Telegraph.

The Wakefield Companion to South Australian History, 2001, Wakefield Press, South Australia

Adelaide – Chinese Population, The Manning Index of South Australian History, State Library of South Australia.

Whitelock, D. (2000). Adelaide: a sense of difference.