Agnes Grant Hay was a great traveller – this was her eighteenth ocean voyage between Adelaide and London, the first being in 1850 when she had migrated to Adelaide with her family as a young teenager. Like many who have changed countries, she struggled to know where she belonged – and was wealthy enough to travel between the two countries all her life.

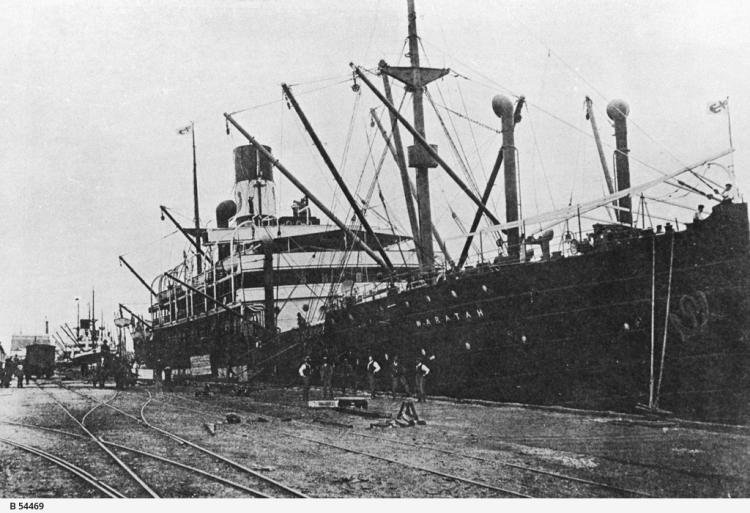

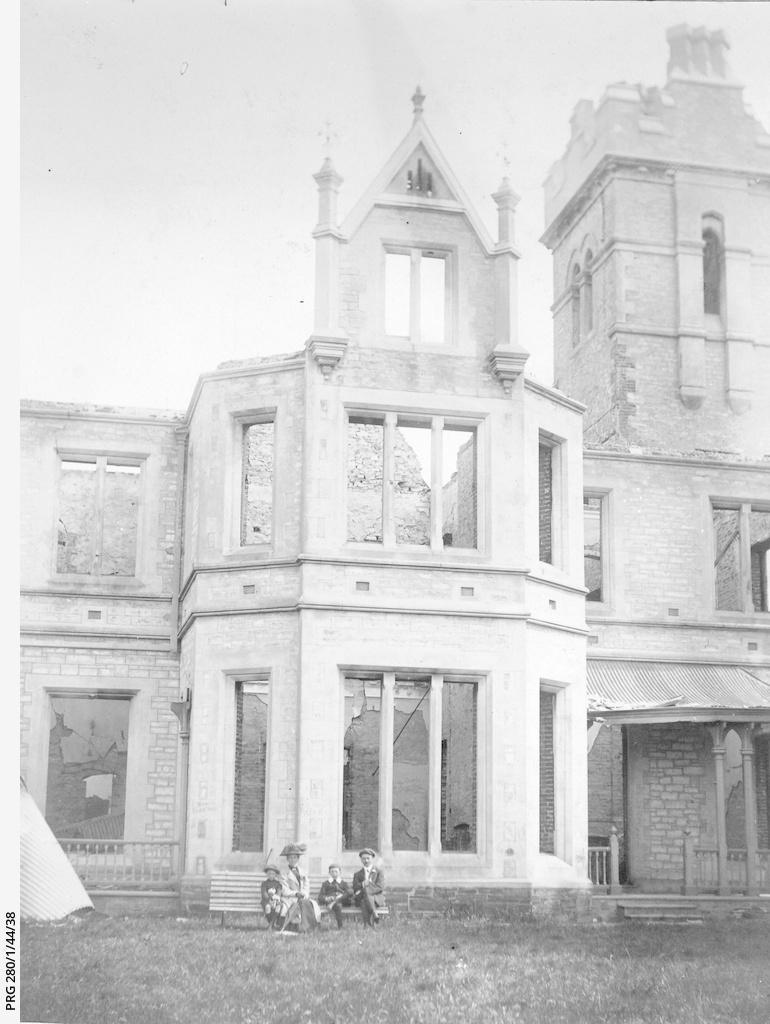

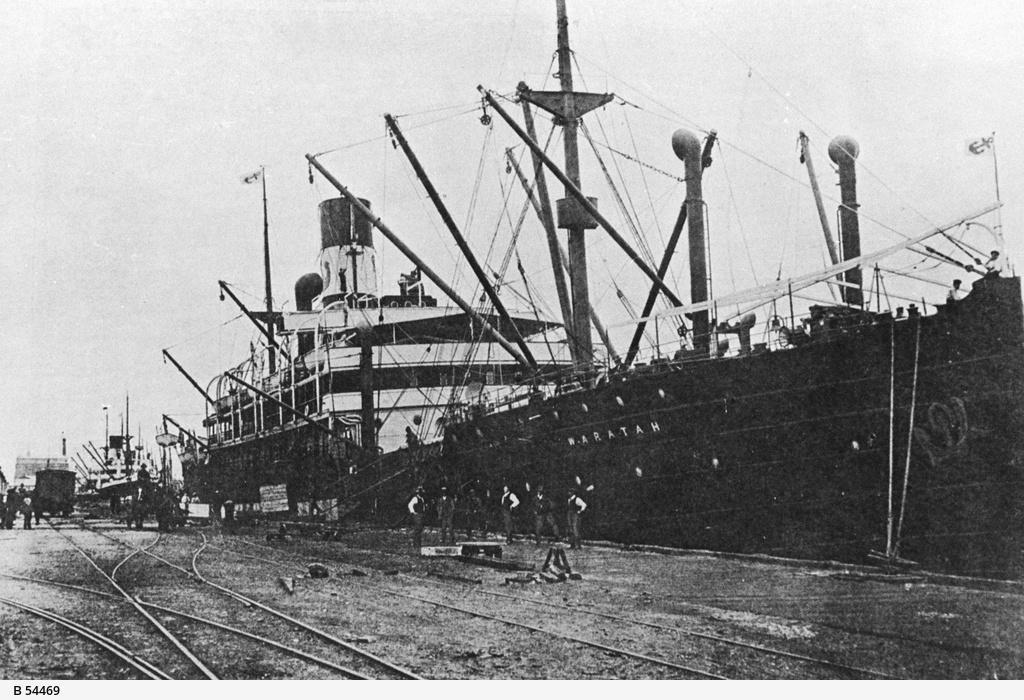

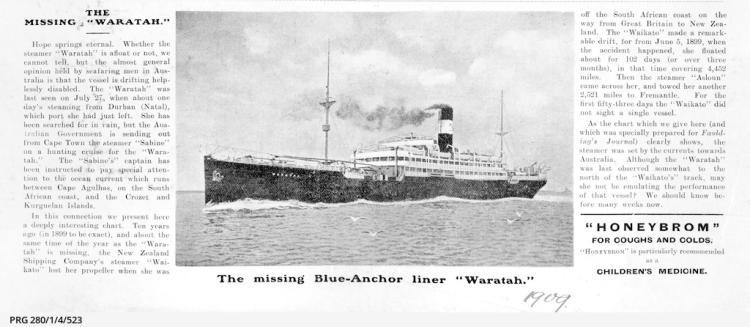

While the complex fire insurance claim for Mt Breckan was being settled, Agnes and Helen decided to return to London, where Mrs Hay’s daughter Gertrude was now expecting a baby. The pair had previously returned to Adelaide aboard the new luxury steamer, the SS Waratah, which had departed London on her maiden voyage on 5 November 1908.

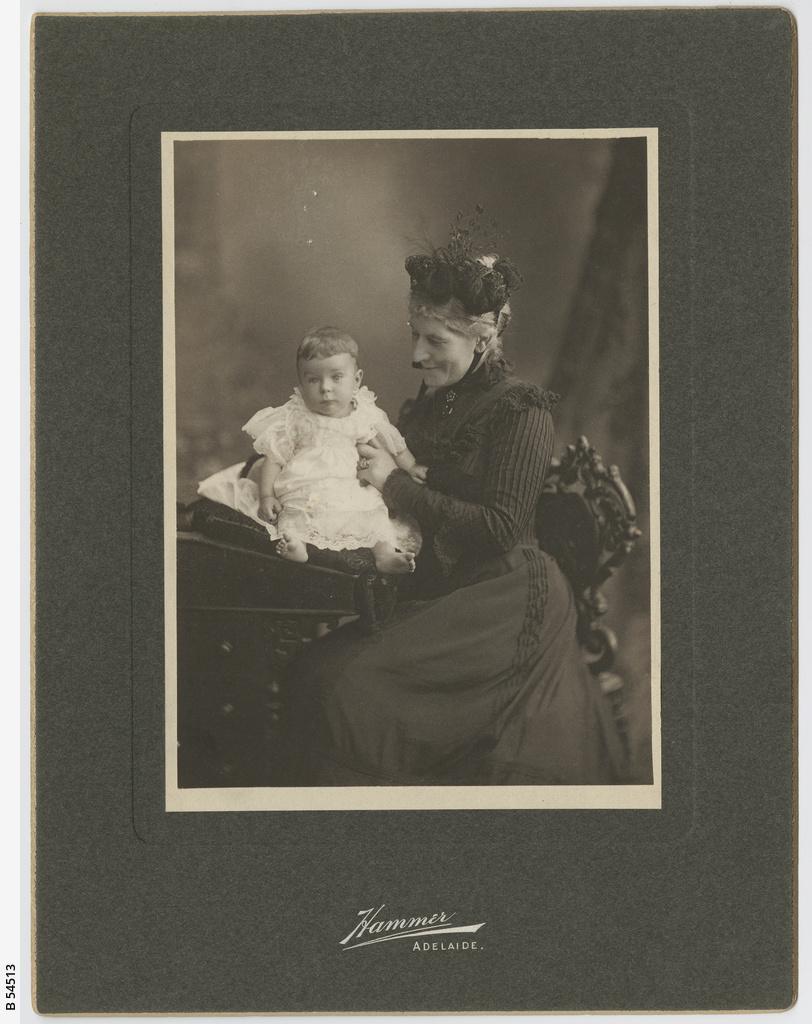

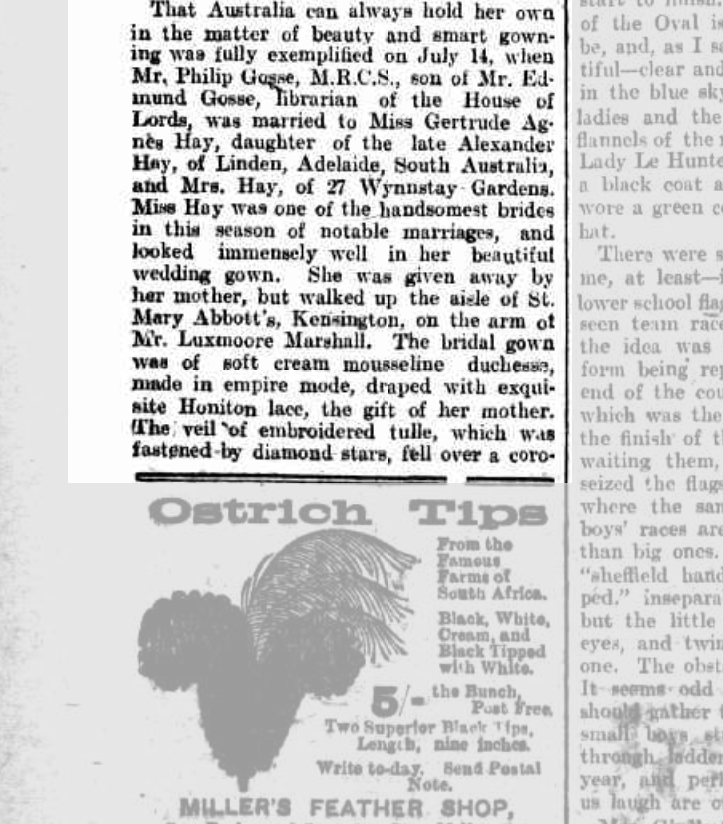

The Waratah was owned by the Blue Anchor Line, then the main competitor to P&O Cruises. Both ran luxury passenger steamers between Adelaide and Britain. Also, on board the Waratah’s maiden voyage were Professor William Bragg and his son Lawrence, later joint winners of the Nobel Prize for Physics. They were in First class, along with Agnes and ‘Dolly’ Hay. The Hays were returning to South Australia after the London society wedding of their older daughter, Gertrude, to a distant cousin, Dr Philip Gosse.

The Waratah was touted as a luxury passenger ship, but she had also been designed to carry cargo, and lots of it. According to the ship’s manifest, in early June 1909, the Waratah arrived at Port Adelaide on its second voyage from England. Here, more than 1100 bags of wheat and 10,710 ingots of copper were loaded. The vessel collected additional cargo in Melbourne, including 8,347 bags of flour, 340 ingots of zinc, and nearly 2,000 bales of wool. In Sydney, 7,803 bars of bullion (1,500 tons ) were loaded, most likely in the form of iron concentrates from Broken Hill, and 2,000 tons of coal. At these three ports, other cargo taken on board included leather, skins, timber, and perishable foodstuffs, including apples. These figures do not include 21 tons of stores and almost 150 tons of ballast water and bilge.

On 7 July, The Waratah left Port Adelaide for England. Agnes and Dolly had booked their First Class berths for the return trip. Mrs Hay, having already published a biography of her late husband, her autobiography and a novel, Malcom Canmore’s Pearl, was writing a novel set in Adelaide. This was tentatively named The Modern Canaan, comparing the European settlement of Australia with the settling of the Jewish people in Palestine. As the Waratah was too large to travel through the Suez Canal, her route was around the bottom of Africa. But the ship never made it to London.

In the Indian Ocean, somewhere off the east coast of South Africa between Durban and Cape Town, the SS Waratah disappeared. The vessel had left Durban on the evening of 26 July 1909. In the early morning of 27 July, she was sighted by another steamer, the Clan MacIntyre, and the two passing ships, as was usual, signalled each other their name and destinations by lamp. This was off the Eastern Cape of South Africa, close to the mouth of the Mbashe River. It was the last confirmed sighting of the lost ship Waratah, although there were several more unconfirmed sightings by other ships as the weather worsened that day. The SS Harlow’s captain reported an excessive amount of fire billowing from a steamship some distance away, followed by two flashes of light which may have been explosions.

An unconfirmed sighting was reported by the captain of the SS Harlow, who observed smoke and running lights from a steamship comparable in size to the Waratah. The vessel was around 12 to 14 nautical miles away. This was at around 5.30 pm on 27 July. The amount of smoke appeared unusually excessive, leading him to speculate that the ship might be on fire. This observation was soon followed by two extremely bright flashes, then nothing.

Later that evening, British passenger liner the Guelph, travelling to Durban, attempted to exchange lamp signals with another ship. The difficult stormy conditions limited visibility, and only the last three letters of the ship’s name, ‘T-A-H,’ could be deciphered.

The SS Waratah was due to reach Cape Town on 29 July 1909, but it didn’t arrive.

Neither the ship nor any of the 211 people on board were ever seen or heard from again. At first, it was assumed that her engines had broken down and the ship was drifting. However, searchers failed to find the vessel or any trace of it. Funds were raised to conduct further searches, but without success. Newspapers of the day were filled with theories about the vessel’s disappearance – in England, Arthur Conan Doyle (author and creator of Sherlock Holmes) conducted a séance to contact the ill-fated passengers.

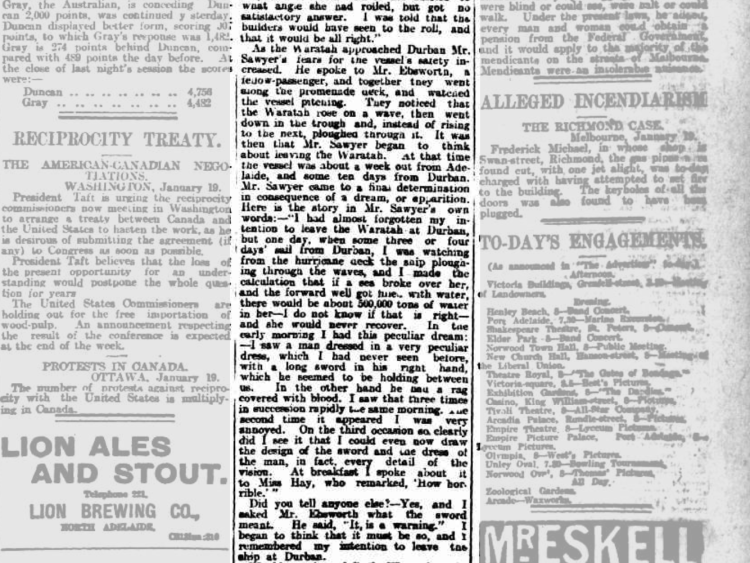

A Court of Enquiry sat in London for 14 months, taking evidence relating to the disappearance. The press described a group of women ‘in deep mourning’ sitting behind the lawyers in the court. Much was made of the testimony of a passenger named Claude Sawyer, an engineer, who left the ship early. He had grown concerned about the vessel’s increasing tendency to list and roll, even in moderate seas. More alarming was a series of frightening dreams that he took as a warning of impending disaster. He reported having spoken to the Hay women, advising them to leave the ship with him at Durban. But they did not.

The Court of Enquiry decided that the steamer had sunk in the first major storm she had encountered. No trace was found of the 92 passengers and 119 crew. No wreckage of any kind was washed up or encountered by the search vessels, including two sent by the Australian government. The investigations, covered between 14,000 and 15,000 nautical miles. There were several unconfirmed sightings of bodies and other objects floating in the ocean or coastal rivers, but nothing verifiable was recovered. It has been suggested that the owners covered up details relating to the experimental design of the ship, unconvincingly stating that nothing out of the ordinary had been reported by the ship’s master after its maiden voyage. To reduce questions about the vessel’s stability and therefore its safety in heavy seas, the vessel’s owners also claimed that the vessel was carrying only a third of its load capacity of just over 3,000 tons when it vanished. The Australian manifests and witness accounts disprove this. On her maiden voyage in 1908, she carried 9,800 tons of cargo, around 90 per cent of capacity. On the ship’s final 1909 voyage, she was laden with between 10,000 and 10,987 tons of cargo, far more than claimed.

Theories continue to come and go about the fate of the SS Waratah and every one of its 211 passengers and crew. These include stories about the theft of gold bullion, supernatural intervention in the form of a curse, and much later, a Bermuda Triangle-type theory located off the African coast. Tony Arbon, co-compiler of the State Library’s maritime collection the Arbon-LeMaistre Collection, believed that the ship’s long coal hatch was stove in by a tremendous wave, which took the ship straight to the bottom.

Alternative ideas suggest that that there was a loss of control of the ship’s steering and power, possibly due to a coal fire or explosion. If, instead of going straight to the bottom near the East African coast, the ship may have drifted away from the regular sea route into deeper water, where it later capsized due to its heavy cargo, the stormy conditions or a rogue wave. Some believe that it floated far into southern waters and was trapped by ice. Either of these two theories would account for the lack of confirmed debris. This could also account for the failure to locate the Waratah’s final resting place, despite multiple efforts. Searchers, then and now, may have been looking in the wrong places.

Alexander Hay’s long-term friend, Samuel Way, like many others, did not believe the steamer could have sunk but instead had drifted into the southern ice pack. This is a theory that has been revived in recent years. Perhaps the melting of the ice at the South Pole will reveal the fate of what has come to be known as ‘Australia’s Titanic.’

Written by Anthony Laube, Team Leader, Collection Development (Published Collections)

Related stories

You might be interested in reading these related Hay family stories.

Love in the stacks: After-glow memories

The State Library, in both its published and its archival collections, holds memories of countless love stories and romances of the past. Buried within letters, diaries and published memoirs are the loves – and lost loves – of many South Australians...

The young lady who left home in 1877

Sleuthing at the State Library using newspaper clippings, three books, inscriptions, newspaper archives, and censuses, pieces together the intriguing story of a run-away in 1877...

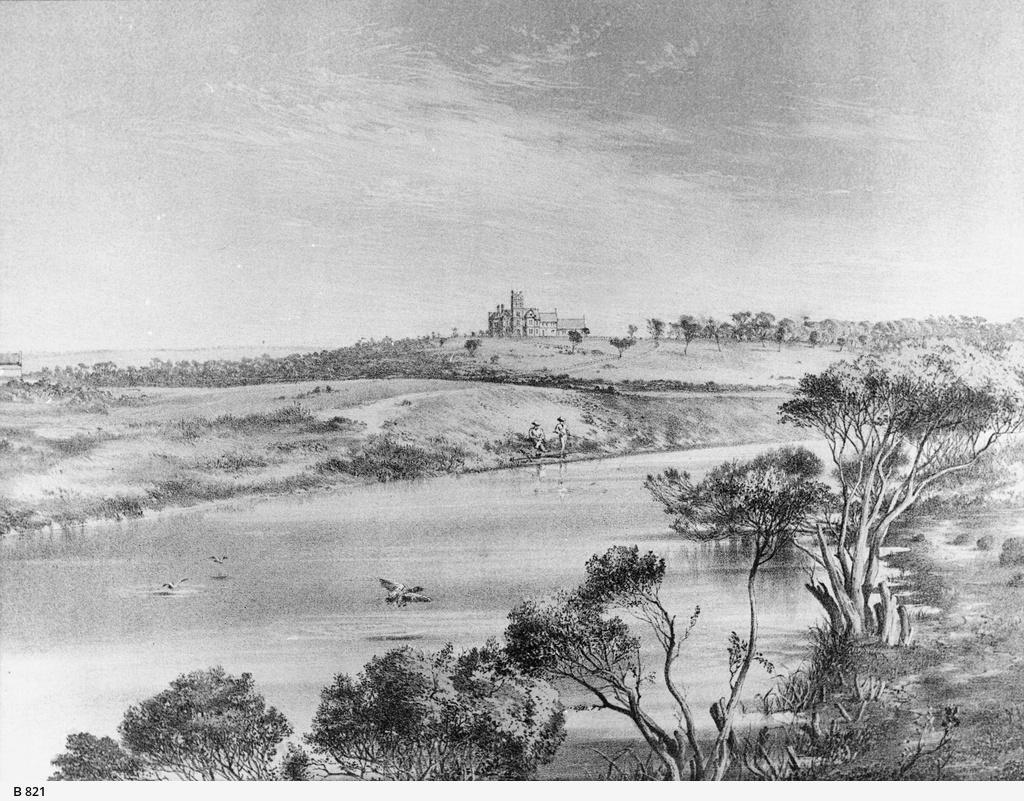

Mount Breckan - from the beginning

A gift for Alexander Hay’s second wife, Agnes Grant (Gosse) Hay, read about the home's history and its society hostess.

A man of many hats: Alexander Hay

Alexander Hay was a merchant, farmer, pastoralist, newspaper proprietor (South Australian Register) and Member of Parliament, in both the upper and lower houses.